2013 Lawyers’ Hall of Fame

Hall of Fame Class – 2013

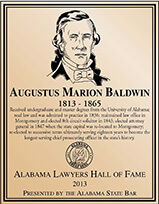

- Marion Augustus Baldwin (1813-1865)

-

Marion Augustus Baldwin was born in Greene County, Georgia on August 13, 1813. He came with his parents to Montgomery County, Alabama in 1816. “Gus” Baldwin was one of the first graduates of the University of Alabama where he received a Bachelor’s degree in 1835. He was awarded a Master of Arts degree from the University in 1843.

Marion Augustus Baldwin was born in Greene County, Georgia on August 13, 1813. He came with his parents to Montgomery County, Alabama in 1816. “Gus” Baldwin was one of the first graduates of the University of Alabama where he received a Bachelor’s degree in 1835. He was awarded a Master of Arts degree from the University in 1843.Baldwin read law in the offices of John A. Campbell (later a United States Supreme Court Justice and Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame 2007 inductee), George Goldthwaite (later an Alabama Supreme Court Justice and United States Senator), and his uncle, Benjamin Fitzpatrick (later an Alabama Governor and United States Senator), and was admitted to the Bar in 1836. He practiced law in Montgomery in partnership with Col. James E. Belser.

In 1843 Baldwin was elected Solicitor of the 8th Circuit, which at the time included Montgomery County. After the state capital moved to Montgomery, he was elected Attorney General in 1847 and was re-elected in 1851, 1855, 1859, and 1863 serving until the end of the Civil War in 1865 when all affiliated Confederate governmental institutions were terminated. Baldwin was a prosecuting attorney for a total of 22 years with 18 of those as the Attorney General of Alabama. He was an effective and well-regarded public servant as evidenced by the fact that the citizens of Alabama recognized his abilities and made him the longest serving Attorney General in the history of the state.

Baldwin was a Democrat, a Mason, and a member of the First Presbyterian Church of Montgomery. After he left the Attorney General’s position he continued to practice law in Montgomery but he died soon thereafter on August 16, 1865 shortly after reaching his 52nd year.

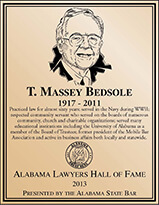

- T. Massey Bedsole (1917-2011)

-

“This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.” So it was said by a first‐term President Franklin Roosevelt in June of 1936, only three short years before the outbreak of the Second World War. Travis Massey Bedsole was an 18‐year‐old college student at the time who had grown up in Grove Hill, Alabama and was pursuing a bachelor’s degree at The University of Alabama. Little did this rising college sophomore know that his destiny was to be intertwined with that of many of his friends and classmates and countless other young men in the years to come. Little did he know that his future and his identity were to be molded on the foreign fields of battle.

“This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.” So it was said by a first‐term President Franklin Roosevelt in June of 1936, only three short years before the outbreak of the Second World War. Travis Massey Bedsole was an 18‐year‐old college student at the time who had grown up in Grove Hill, Alabama and was pursuing a bachelor’s degree at The University of Alabama. Little did this rising college sophomore know that his destiny was to be intertwined with that of many of his friends and classmates and countless other young men in the years to come. Little did he know that his future and his identity were to be molded on the foreign fields of battle.During that time, Mr. Massey, as he would later be affectionately known, was busy earning accolades like election to the University’s chapter of Phi Beta Kappa before being tapped to become a Jason. His undergraduate achievements then earned him a place in The University of Alabama School of Law’s class of 1941. After law school Mr. Bedsole confronted his destiny head‐on by enlisting in the United States Navy, doing his part in the war for freedom what must have seemed many worlds away to a young man from Grove Hill.

As a navy aviator, Mr. Bedsole fought in the Pacific Theater at Midway and Guadalcanal and ranked as a lieutenant colonel by the end of the war. He returned home to South Alabama, moved to Mobile, and joined the law firm that would later bear his name, Hand, Arendall, Bedsole, Greaves & Johnston. Over his career spanning more than a half century, this judge’s son became the embodiment of “lawyers rendering service.” Mr. Bedsole became an active member of the First Baptist Church of Mobile and lived his faith daily through volunteerism and service to the Mobile Rescue Mission, fundraising for civic projects through the Community Chest, and involvement with the Southern Seminary Foundation.

Mr. Bedsole perhaps left his greatest mark through leadership in education. For almost forty years, he served as a trustee of the University of Mobile. He became chairman of the board in 1979, and was later given the honorary title chairman emeritus in recognition of his years of service to the institution. While Mr. Bedsole was also an original trustee of the Wright School for Girls, his contributions to education were not limited to the Mobile area. He was chosen to serve on the Board of Trustees of The University of Alabama System in 1979 and continued to hold that post for ten years.

Throughout his career, Mr. Bedsole enjoyed the dedication of his wife of 64 years, Mrs. Martha Oliver Bedsole, and his two children, Travis Bedsole, Jr. and Curry Bedsole Adams Although our state and the Mobile community, in particular, lost a champion on the first day of January, 2011, Massey Bedsole’s legacy lives on as an inspiration for each of us to dedicate our time and our talents to the benefit of others. As has been said many times, Mr. Massey was the embodiment of the hard work and dedicated service that define the Greatest Generation.

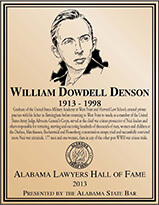

- William Dowdell Denson (1913-1998)

-

“Endow us with courage that is borne of loyalty to all that is noble and worthy, that scorns to compromise with vice and injustice and knows no fear when truth and right are in jeopardy.” William Dowdell Denson must have internalized these words of the Cadet Prayer while matriculating the United States Military Academy, but it is doubtful he could have appreciated at the time the extent to which those words would form the foundation of his selfless sacrifice to our country and to the legal profession.

“Endow us with courage that is borne of loyalty to all that is noble and worthy, that scorns to compromise with vice and injustice and knows no fear when truth and right are in jeopardy.” William Dowdell Denson must have internalized these words of the Cadet Prayer while matriculating the United States Military Academy, but it is doubtful he could have appreciated at the time the extent to which those words would form the foundation of his selfless sacrifice to our country and to the legal profession.William Dowdell Denson was born in Birmingham, Alabama, on May 13, 1913, and inherited an ancestral love of the law. His paternal grandfather was a justice on the Alabama Supreme Court and his father, also an attorney, ran a highly respected firm in Jefferson County.

Denson graduated from West Point in 1934 and then from Harvard Law School in 1937. Following receipt of his law degree, Denson joined his father’s law firm in Birmingham.

Denson practiced with his father until the beginning of World War II in 1941, whereupon he returned to West Point to teach law, exhorting young cadets to honor the Constitution and human rights, principles upon which American democracy was founded. Denson was then whisked from teaching law at West Point to leading the prosecution in the largest series of Nazi trials in history.

As the chief prosecutor in the “Dachau trials,” Denson used a makeshift courtroom on the grounds of former Camp Dachau to prosecute men and women who operated concentration camps and implemented the “Final Solution” for Adolf Hitler. The defendants at Dachau, Mauthausen, Buchenwald and Flossenburg stood accused of torturing, starving and executing hundreds of thousands of men, women and children. Denson led a brilliant prosecution against those defendants, but not without it taking a severe personal toll on the 32 year old. Nearly two years of constant exposure to unconscionable crimes against humanity, with barely a day or two to recover between trials, punished Denson mercilessly. His wife divorced him, his weight dropped from 168 to 116 lbs., he developed a palsy-like tremor in his hands, and he collapsed from exhaustion. However, he was able to rally, and after a few weeks in an army hospital, returned to the courtroom to win 100% convictions against the defendants.

Denson’s goal was not to impart a “victor’s justice” and win at any cost, but to win according to due process of law, as he had taught his cadets. History, he knew, would judge the army’s actions in court and determine whether he had succeeded in demonstrating the power of the law to deal effectively with heinous, unprecedented crimes. Denson’s record during those two years of proceedings remains unchallenged; he tried and convicted more Nazi war criminals than any other lawyer in history–177 men and one woman in the main Dachau trials–the largest series of war crimes in history.

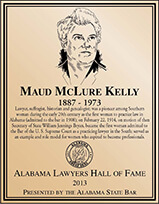

- Maud McLure Kelly (1887-1973)

-

Maud McLure Kelly was born in Talladega County, Alabama on July 10, 1887. She was the daughter of Richard Bussey Kelly, a lawyer and politician, and his wife Leona Bledsoe Kelly. Even as a young child Maud Kelly was fascinated by the law. She graduated from law school at the University of Alabama in 1907 when she was only 19. However, she found unequal treatment for women in the law of Alabama from the earliest moments of her legal career. The Code of Alabama stated that a lawyer could be licensed by presenting “his” law diploma from the University of Alabama. No woman could technically practice law until the Code was amended by the legislature on November 26, 1907, to read “his or her” law diploma. Kelly became the first woman to have a law practice in Alabama.

Maud McLure Kelly was born in Talladega County, Alabama on July 10, 1887. She was the daughter of Richard Bussey Kelly, a lawyer and politician, and his wife Leona Bledsoe Kelly. Even as a young child Maud Kelly was fascinated by the law. She graduated from law school at the University of Alabama in 1907 when she was only 19. However, she found unequal treatment for women in the law of Alabama from the earliest moments of her legal career. The Code of Alabama stated that a lawyer could be licensed by presenting “his” law diploma from the University of Alabama. No woman could technically practice law until the Code was amended by the legislature on November 26, 1907, to read “his or her” law diploma. Kelly became the first woman to have a law practice in Alabama.Maud McLure Kelly practiced law in Birmingham. On February 22, 1914, on motion of then Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, she became the first woman admitted to the Bar of the United States Supreme Court as a practicing lawyer in the South. In 1917, during World War I, Kelly moved to Washington, D.C. and first worked for the War Department and then served on the legal staff of the Land Office of the Department of the Interior. After the war ended she decided to stay in Washington for a few years but she returned to practice in Birmingham in April, 1924. She retired from her practice in 1931 to spend more time with her mother who was ill.

Maud McLure Kelly was ever an achiever and a doer. She held leadership positions in a number of historical organizations, the American Legion Auxiliary, the Democratic Party, and the Birmingham Public Library Board. In 1943 she moved to Montgomery and became Historical Materials Collector for the Department of Archives and History until 1956 when family responsibilities again required her to retire. Until her death she continued as a private researcher and genealogist.

Maud McLure Kelly died on April 2, 1973. Her contribution as Alabama’s first practicing woman lawyer can be summarized in her own words:

“For such a long time I was the only woman practicing law in the state that I had to be a model of femininity as well as the best possible lawyer, since whatever way I acted would involve the women after me. That their paths have been smoother because I was so careful, I am confident…. I used to wonder, if, when I had passed on my way, the later comers would ever realize how much I thought of them, and how I tried to so conduct myself that things would be easier for them than they had been for me.”

According to her biographer, Cynthia Newman, Maud McLure Kelly did fulfill her responsibilities to the younger generation of women lawyers. She left behind a record of integrity and community service worthy for induction into the Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame.

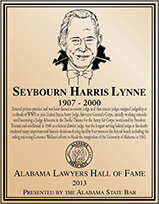

- Seybourn Harris Lynne (1907-2000)

-

“I love the people of Alabama.” Those words written by Judge Seybourn Harris Lynne in a landmark decision desegregating the University of Alabama typified the beloved jurist, lawyer and community leader who was a legal giant by every measure and a champion of the Rule of Law.

“I love the people of Alabama.” Those words written by Judge Seybourn Harris Lynne in a landmark decision desegregating the University of Alabama typified the beloved jurist, lawyer and community leader who was a legal giant by every measure and a champion of the Rule of Law.Lynne was born in Decatur, Alabama, on July 25, 1907. He attended Auburn University, where he graduated with highest distinction and starred in both football and track. He thereafter earned his law degree in 1930 from the University of Alabama. Upon graduation from law school, Lynne practiced law for four years with his father. In 1934, Lynne was elected judge of the Morgan County Court, his first call to service. Lynne remained in that position until January 1941, when he became judge of the Eighth Judicial Circuit of Alabama.

In December 1942, Lynn heard another call to service – this time, from our country to serve in our military in World War II. Lynne received the Bronze Star and earned the rank of Lieutenant Colonel before resigning his commission in November 1945.

In 1946, President Harry S. Truman appointed Lynne to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama. In 1953, Lynne became chief judge of that court and in 1973 became senior judge, a role in which he actively continued to serve until his death in 2000. At the time of his death, Lynne was the longest serving federal judge in America, having dedicated over sixty years of distinguished service to the judicial system, the last fifty-four of which were in service as a federal district court judge.

Lynne was well known for his keen, analytical mind, his superior scholarship and preparedness, his compassionate spirit, his impeccable integrity, and the efficiency with which he handled his substantial docket.

Judge Lynne authored many landmark decisions. One of those decisions was submitted during the racially-charged climate of 1963 in which Lynne enjoined the Governor of Alabama from interfering with the enrollment of African-American students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, at the University of Alabama. The opinion is symbolic of his characteristic logic and empathy. It is a demonstration of his moral courage. It is evidence of his efforts to inspire Alabamians to a higher level of life and to “love thy neighbor.”

Lynne served his community. He was a lifetime deacon, a trustee and Sunday School teacher for over forty years at Southside Baptist Church. He was also a trustee of the Crippled Children’s Clinic of Birmingham and a number of foundations. And he was a former president of the Alabama Alumni Association.