2014 Lawyers’ Hall of Fame

Hall of Fame Class – 2014

- Walter Lawrence Bragg (1835-1891)

-

Walter Lawrence Bragg was born on February 25, 1835, in Lowndes County, Alabama. He was the grandson of Peter Bragg who fought in the Revolutionary War and was a cousin of Confederate General Braxton Bragg.

In 1843, Bragg’s father moved the family to Arkansas where they resided until 1861. Young Walter studied law at Harvard, but left after three terms due to the unpleasant relations among students from various sections of the country prior to the Civil War. After leaving Harvard, he read law and was admitted to the bar in Arkansas in 1856.

In April 1861, he enlisted in the Sixth Regiment of the Arkansas Infantry, serving and seeing action throughout the war as a Captain. He was present at the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston’s army at Greensboro, North Carolina, in April 1865. Thus, he served for four full years in the Confederate Army.

Following the war, Bragg settled in Marion, Alabama, where he practiced law there and in Montgomery, having moved to Montgomery in 1871. He served his native state as Chairman of the Alabama Democratic Executive Committee. While Chairman, he led the Democrats to victory in the election of 1874. In 1879, he was an organizer and the first president of the Alabama Bar Association.

In 1881, Governor Rufus W. Cobb appointed Bragg to the newly created Alabama Railroad Commission, the body charged with regulating the railroads of Alabama, and he served with distinction as its first chairman. His efforts as a regulator in Alabama received national attention and he became an original appointee by President Grover Cleveland to the Interstate Commerce Commission. He served on this federal board from March 22, 1887, until his death on August 21, 1891, at Spring Lake, New Jersey. At the time of his death he was 56 years old. He is buried at Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery.

Walter Lawrence Bragg served as a soldier, a lawyer, a political leader, a leader of the bar and a state and national regulatory commissioner. For all of these accomplishments he is now recognized as a member of the Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame.

- George Washington Lovejoy (1859-1933)

-

George Washington Lovejoy was born a slave in Coosa County, Alabama, in February of 1859. As one of 11 brothers and sisters, he went to work in the cotton fields at the age of seven. At age ten, he began attending school for two months each summer. While in school, he learned the rudiments of reading. At 21 years old, Lovejoy found a job on a farm and began saving money. After three years, he managed to accumulate $25 and enrolled in the Swayne School in Montgomery, founded by General Wager Swayne who was head of Alabama’s Freedmen’s Bureau, to educate former slaves.

While at the Swayne School, Reverend Robert C. Bedford, a trustee at Tuskegee Institute, took Lovejoy under his wing and convinced him to enter the Institute. At Tuskegee, Lovejoy was befriended and encouraged by the school’s founder Booker T. Washington to whom Lovejoy confessed his dream of becoming an attorney.

Upon graduation from Tuskegee in 1888, Washington contacted William C. Reid, the first African-American attorney to practice in Portsmouth, Virginia, who agreed to teach Lovejoy the law. But first, Lovejoy had to earn enough money to make the trip. After teaching for eight months, he saved enough to cover his travel expenses.

Lovejoy arrived in Portsmouth, with $1.25 left in his pocket. He found a day job at the U.S. Navy Yard so that he could cover his expenses while he read law with Reid at night. After three years of study, Lovejoy returned to Alabama. Having tried for five months to obtain a sponsor, Lovejoy finally succeeded in getting an attorney in Macon County to recommend him to the Chancery Court for examination. He was examined in open court before all the practicing attorneys of the Macon County bar, passed the examination and was granted a license to practice law in the state of Alabama.

Lovejoy opened his office in Mobile on September 8, 1892, and practiced law in the Port City for nearly thirty years. In 1899, he served as one of Liberia’s consuls resident in the United States. He died in Mobile in 1933, at the age of 74 and was buried in Magnolia Cemetery. The road from slavery to the bar is difficult and one that few Alabamians have traveled. George Washington Lovejoy did so and is remembered for his perseverance, dedication and courage.

- Albert Leon Patterson (1894-1954)

-

Albert Leon Patterson was born in 1894 in New Site in Tallapoosa County, Alabama. As a young man he worked as a day laborer and finished high school in Fairfield, Texas. He served in the Third Texas Infantry in World War I. He was wounded near St. Etienne and awarded France’s medal for valor. He suffered from his war wounds and used a cane for the rest of his life. After the war, he returned to Alabama and completed a two-year teacher’s certification from Jacksonville Normal School. He served the education field as a principal in Clay and Coosa counties. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Alabama in 1924, and in 1925 he received his law degree from Cumberland Law School, then at Lebanon, Tennessee. He began practicing law in Opelika in 1927 and subsequently moved to Phenix City in 1933.

Phenix City, Alabama, was known as the “wickedest little city in America.” Organized crime had infested the city and Russell County by the mid-1950s. Patterson served in local offices and the State Senate from 1947-1956. He ran for Lieutenant Governor in 1950, but was defeated by influential politicians and organized crime. He became an early member of the Russell County Betterment Association whose purpose was to fight corruption in Russell County. He ran for Attorney General in 1954 with the support of this group and many others. After an exhaustive multi-candidate primary, Patterson led the ticket but faced a runoff. In a disputed election count he was named the winner on June 10. On June 18, as he was leaving his office in Phenix City around 9:00 p.m., he was shot three times and died at the scene.

Governor Gordon Persons declared partial martial law and ordered the Alabama National Guard to take over law enforcement from local police and sheriff’s deputies. Special prosecutors and Judge Walter B. Jones were dispatched to replace the local judiciary. Ultimately, organized crime was dismantled in six months. A total of 734 indictments were returned against law enforcement officers, local business owners and elected officials. The Circuit Solicitor (now District Attorney), Chief Deputy and the outgoing Attorney General were indicted for Albert Patterson’s murder. The Chief Deputy was convicted. Albert Patterson’s son, John Patterson, was named the Democratic nominee in place of his father and he was elected Attorney General of Alabama in 1954. He was elected governor of Alabama in 1958.

Albert Patterson had predicted that it would take 10 years to eradicate the vice and corruption in Phenix City. After his tragic death it was cleaned up in a matter of a few months. His assassination was the impetus for reform and such corruption has not recurred in Alabama. Hopefully, it never will. For his crusade for good government, Albert Patterson is a worthy inductee to the Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame.

- Sam C. Pointer, Jr. (1934-2008)

-

He “applied the law as he found it; and he did this always without bias, prejudice or sympathy for or against any party.” Those words, written by his longtime colleague and friend, James C. Hancock, exemplifies the professional legacy of Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame inductee Sam C. Pointer, Jr.

A native son of Birmingham, Alabama, born on November 15, 1934, Pointer dazzled in the classroom. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Vanderbilt University, at the top of his class from the University of Alabama Law School and with one of the highest grades ever awarded from the New York University Graduate School of Law.

Pointer put those stellar marks to use first in the summer of 1958 when he began practicing law with his father, where he remained until he was appointed by President Nixon in 1970 as a Federal District Judge to the Northern District of Alabama. At the time he took the oath of office at the age of 35, he was the youngest person in the country serving as a federal district judge. His service in that capacity continued for 30 years, the latter 17 of which were in service as Chief Judge of the Northern District of Alabama.

Sharp, conscientious and attentive to his duties, Pointer was a natural fit for service as a federal district judge. Judge Hancock remarked, “Very few people are aware of the extremely high esteem judges, educators and lawyers throughout the country who came in contact with Sam had for him. I want to make it perfectly clear that his great intellect and ability to express himself in writing is legendary among judges and lawyers alike.”

He was also humble. “He was always the smartest person in the room, but he never made others feel inferior about it,” it has been said of Pointer.

Pointer handled some of the toughest cases of his time involving school desegregation, employment discrimination and jail/prison conditions. His intellect also made him well suited to handle the most complex civil cases. He tried the Cast-Iron Pipe Antitrust Litigation, the first class action for damages ever tried in the United States; the National Steel Industry Employment Litigation and the Plywood Antitrust Litigation, the 3rd class action for damages tried in the United States; as well as the more than 26,000 Silicone-Gel Breast Implant cases that were granted MDL status in the early 1990s. Diligently following United States Supreme Court and appellate court precedent, Pointer made courageous, correct and controversial rulings in these cases, some of which put him at great personal risk and required 24/7 U.S. Marshal protection for him and his family.

Pointer was particularly revered by his law clerks who not only saw him in action in difficult, complex and heated disputes, but experienced him on a very personal level. They got to know the man. One of those clerks, Mac Moorer, observed, “Every party to a lawsuit, every attorney, every court reporter, every docket clerk, no matter what your station in life, Judge Pointer always treated everyone with the same dignity and courtesy and respect. Every person had worth and value to him, and his clerks quickly learned that we were expected to treat everyone the same way that he did.”

Judge Pointer’s influence carries on a legacy of respect for others through the 58 law clerks that were fortunate enough to spend time with him during those years. While they may have questioned those “mandatory” daily lunches that varied widely from hot dogs to barbecue, the inescapable conclusion is that Pointer “made the world a better place.” He died on March 15, 2008. The Alabama State Bar is honored to induct Sam C. Pointer, Jr., into its Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame.

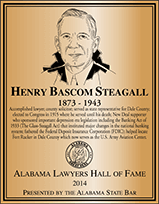

- Henry Bascom Steagall (1873-1943)

-

Henry B. Steagall was the youngest of four children born to William and Mary Jane Steagall. His father was a physician who also served in the Alabama State Senate. The young Steagall studied law at the University of Alabama, graduated in 1893 and was admitted to the bar that year. He began his practice in Bullock County, but returned to Dale County where he was born and to begin his political career. He married Sallie Thompson in 1900 and during their eight year marriage they had five children. Sallie died at the age of 28 and Steagall never remarried, devoting the rest of his life to public service.

He was appointed by Governor Joseph F. Johnston as the County Solicitor for Dale County and served in that position from 1898-1906. In 1906, he was elected to the Alabama Legislature. Governor B.B. Comer then appointed him as the prosecutor for the Third Judicial Circuit in 1907, and he was elected for a full term from 1910-1914. During that time, he also served on the state’s Democratic Executive Committee from 1906-1910 and was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1912.

In 1914, Steagall was elected to the United States House of Representatives from Alabama’s Third Congressional District. He was then re-elected for 14 more consecutive terms to Congress. In 1931, he was named chairman of the influential House Committee on Banking and Currency. He rose to this position during the Great Depression. Herbert Hoover was president and the stock market had just collapsed in 1929. Thousands of U.S. Banks had failed, understandably causing the public to question the dependability of the U.S. banking system. Southern banks were particularly vulnerable because of the low prices of cotton.

Despite the need for reform, a bill designed to regulate banks and insure deposits was withdrawn from Congressional consideration in 1932, so it would not be an election year issue. Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated Hoover in the 1932 election and one of his first acts was to declare a National Bank Holiday from March 6 to March 9, 1933, temporarily closing the banks for assessment and to determine the viability of the banks. As chair of the Banking and Currency Committee, Steagall used his position to push through the Emergency Bank Act of 1933, which legalized the National Bank Holiday and set standards for the reopening of only banks in good financial condition.

Reports of the time say that Steagall had the only copy of the legislation in the House and that he waived it over his head admonishing the House to pass the bill, which it did with less than one hour of debate and no amendments. Steagall was then instrumental in adding insurance requirements to the 1933 Banking Act, also known as the Glass-Steagall Act, creating the FDIC as well as separating investment banking from commercial banking. In 1937, through the Wagner-Steagall National Housing Act, Steagall played a pivotal role in creating the U.S. Housing Authority to oversee low-income public housing.

Steagall continued to serve as chair of the Banking Committee into the early years of World War II. He died in November 1943 in office in Washington, D.C., from a heart attack. Throughout his long political career Henry B. Steagall embodied the motto of the Alabama State Bar – “Lawyers Render Service”.